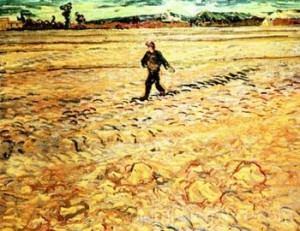

The Sower (Part 1)

This is the first part of a three-part series on the parable of the sower, focused on the version of that parable that appears in Mark 4. In the second installment I will give my analysis of the parable itself, and in the third I will share some lessons I think the parable has for us.

This is the first part of a three-part series on the parable of the sower, focused on the version of that parable that appears in Mark 4. In the second installment I will give my analysis of the parable itself, and in the third I will share some lessons I think the parable has for us.

To understand the parables of Jesus is crucial for anyone seriously interested in knowing what Jesus taught during his time on earth, since the New Testament gospels are the main documents that preserve the teachings of Jesus, and parables make up a large portion of these teachings – about thirty-five percent in the synoptic gospels (Snodgrass, 22). Jesus was clearly a teller of parables, so any student of Jesus’ teachings needs to come to terms with the parables. For people in UBF, understanding the parables takes on additional significance since the gospels make up the bread and butter of our theological understanding. Sunday sermons and correlated Bible studies typically move passage-by-passage through a book of the Bible, and the general pattern of book selection in many UBF chapters takes one of the gospels, then another OT or NT book, and then back to another of the gospels, alternating between a gospel and other books of the Bible. Knowing, then, what Jesus’ parables are supposed to be doing can only help us as we seek to follow him.

So what is a parable, anyway? The New Testament’s use of the Greek word parabole, and the Hebrew word mashal (most frequently translated parabole in the Greek version of the Old Testament), actually cover a wide range of literary forms that precision-oriented people would want to distinguish from each other. Metaphors (“You are the salt of the earth” (Mt 5:13)), aphorisms (“Let the dead bury their own dead” (Lk 9:60), proverbs (“Physician, heal yourself!” (Lk 4:23)), allegories (e.g. the two eagles and the vine in Ezekiel 17), simple comparisons or similitudes (“Like a dog that returns to his vomit is a fool who repeats his folly” (Prov 26:11)), extended narrative comparisons (e.g. the parable of the prodigal son in Lk 15) and more can all be referred to as “parables” in the biblical sense of that word.[1]

New Testament scholars who do research on the parables disagree with each other on various points concerning both the nature and the function of parables. I won’t be able to go into much detail on the fine points of this vast literature, but will simply present what I see as a good working definition of the term “parable,” and a good general characterization of how parables are supposed to work. For the purposes of understanding the sort of thing the parable of the sower is (and what most of the other texts we usually think of as parables are), it will be sufficient to define a parable as an extended comparison in narrative (story) form with a beginning, middle and end, that compares some event from human experience or nature to something else (usually to some aspect of the kingdom of God). Whatever else the function of parables might be, it is clear that Jesus used them to teach. Many scholars see the theme of Jesus’ teaching, especially in the parables, as concentrated on the overarching theme of the kingdom (or reign) of God. From this point of view we can explain the wide variety of different parables by noting that, just as a king does many different things, so to does the King whose kingdom Jesus describes. So the kingdom of this King can be compared to many different things, each of which is intended both to give us insight and to move us to the sort of faith, decision and action appropriate for subjects of the King.

A core question to ask about the parables is how we should read them. The rest of this installment will investigate this question. To get our minds around the different possible ways of reading a parable, it is useful to think of parables as narrative worlds. Part of what you do when you tell a story is to generate a world of meaning. For example, J.K. Rowling, in writing the Harry Potter series, created a narrative world that is populated by various fictional characters (e.g. Ron Weasley, Lord Voldemort), institutions and settings (e.g. Hogwarts School, Ministry of Magic), and that has its own history. The parables of Jesus are obviously much shorter than the fantasy novels of Rowling, Tolkein or C.S. Lewis, and the narrative worlds generated are relatively sparsely populated. The characters in Jesus’ parables do not get developed much, and he includes only the details needed to make his point. Still, they generate small narrative worlds. An interesting thing about Jesus’ parables is that they are stories within stories. Each one occurs within the larger narrative context of a gospel, which is itself a story (in this case a story whose main character is Jesus), and so a distinct narrative world. Parables, then, are stories embedded inside of bigger stories. We can take this further: the gospels themselves are part of the New Testament, and the New Testament is one part of the two-part canonized work Christians call the Bible. It is possible to see the entire Bible, even with all its diversity, as generating an over-arching narrative world.

Each of these world-levels – (1) the parable itself, (2) the gospel as a whole, (3) the whole of Scripture – can play a role in how we read and understand any given parable. Some scholars have wanted to pull the parables out of their narrative contexts and examine them in isolation (focusing exclusively on Level 1). The motivation for reading the parables in this way is to get at the “original” parable, as Jesus actually told it in its historical, first-century life setting. People worry that when the author of the gospel recorded the parable, he adapted and shaped it to fit his own theological agenda, and so lost the function and intention of the historical Jesus. The effort to understand how Jesus’ first-century audience would likely have heard his parables brings an additional level into play: (4) the parable within the first-century cultural context of Jesus’ life and ministry. Reading the parables informed by what we know about Jesus’ cultural context and social setting can enable us to fill in the unspecified details of the parabolic worlds more accurately.

Another worry that drives these scholars comes from the tendency of parable interpreters in the past to “allegorize” the parables. Allegorizing means treating the parable as a secret code that needs to be deciphered, and resolving its meaning in ways disconnected from the actual text and the original intention of telling the parable. The way Augustine interpreted the parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:29-37) often gets cited as a particularly bad example of this. Augustine says the man who gets beat up is Adam, the thieves are the devil and his angels, the priest and Levite are the priesthood and ministry of the Old Testament, the Samaritan is Jesus, the donkey is the incarnation, the inn is the church and the inn-keeper is Paul, and this goes on for pretty much every single object in the story. Is this what Jesus meant when he originally told the story? Allegorizing introduces still another level or two of meaning from which parables can be read: (5) the parable within the network of Christian theological doctrines, or even (6) within the network of universal truths about human beings, God and the world. But even if we agree that allegorizing in an overly imaginative way is a problem, it seems clear that we shouldn’t get rid of it altogether. As we will see in the parable of the sower, either Jesus himself or the gospel writers (or both) allegorized to some extent (see Mk 4:14-20), and in doing so followed a practice common in Old Testament writings and in other writings around the time of Jesus and the early church.

In the next installment, I will try to show how reading the parable of the sower at each of the levels of meaning (1)-(6) can help us to get a deeper understanding of the text, but at the same time can limit us and lead us astray if we aren’t careful.

[1] All references to Scripture are to the NIV 1984 version.

Good article Andy! Cant wait for your interp

thank you Andy, wait for next instalement!